Our breakout session on privacy was well-attended, with about 15 people, mainly coming from backgrounds in healthcare, insurance, and the like. There was a quite active discussion.

Alpha release privacy icon indicating "your data may be bartered or sold".

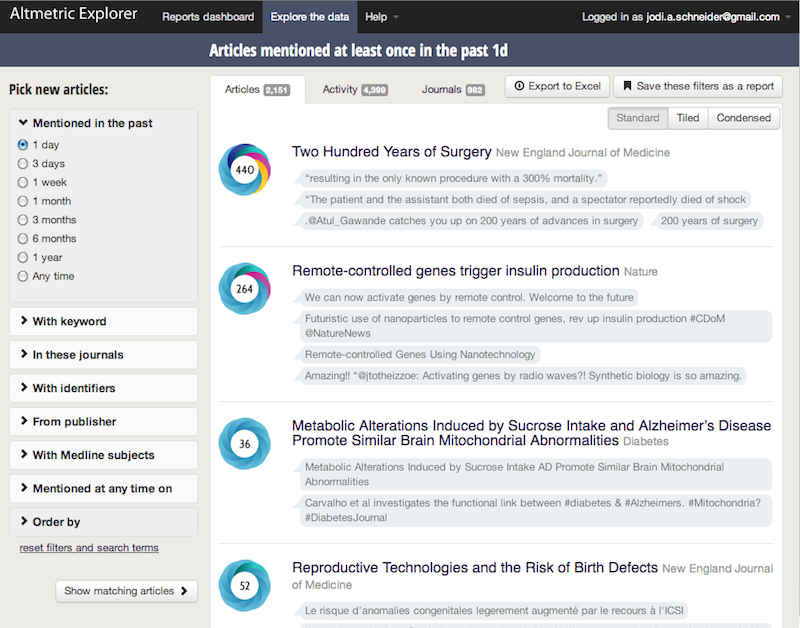

In addition to the questions I shared earlier, I was asked to give pointers to a few things I mentioned.

Aza Raskin asked, Could we make privacy policies as simple as CreativeCommons has made licensing? There’s now an alpha release of the privacy icons. Earlier info about the project is also in Aza’s blog.

Several people were familiar with “Say Everything“, a 2007 NY Magazine piece on how publicly many young people were living their lives:

…the idea of a truly private life is already an illusion. Every street in New York has a surveillance camera. Each time you swipe your debit card at Duane Reade or use your MetroCard, that transaction is tracked. Your employer owns your e-mails. The NSA owns your phone calls. Your life is being lived in public whether you choose to acknowledge it or not.

So it may be time to consider the possibility that young people who behave as if privacy doesn’t exist are actually the sane people, not the insane ones.

But I came across that article in conjunction with a story about a teenager whose publicity had caused her embarrassment and harm, when a sports blogger posted her picture along with a 4-paragraph note excerpted as “Meet pole vaulter Allison Stokke. . . . Hubba hubba and other grunting sounds.”

…what could she do now, when a search for her name in Yahoo! revealed almost 310,000 hits? “It’s not like I could e-mail everybody on the Internet,” Stokke said.

She felt like

Her body had been stolen and turned into a public commodity, critiqued in fan forums devoted to everything from hip-hop to Hollywood.

danah boyd, who has extensively researched teens and the Internet, has also written and spoken sagely about privacy.

Here’s an except from a talk she gave: “The Future of Privacy: How Privacy Norms Can Inform Regulation”

All too often, folks presume that privacy is about hiding information or controlling access to information. This is a very limited view. For teens, privacy has more to do with feeling safe and in control of a situation, trusting people and systems, and leveraging an understood context for intimacy.

Let me ground this in an example. If I’m dealing with an illness, I’m not hiding it from people just because I’m not talking about it. If I choose to share my illness, I’m probably not going to start by standing up in the middle of the town square and shouting loudly to everyone who could possibly hear that I’m ill. I may start by gathering my family and sharing in an intimate situation where I feel supported. I open up to them, make myself vulnerable, in exchange for support. This is privacy. I also have expectations about that social situation. I expect my family to respect the situation in which I shared something deeply personal. I _trust_ them to understand how far that information is supposed to be spread. Any one of them is capable of breaking my trust, telling someone against my wishes and expectations, but what’s at stake is the relationship. My agency, my power, in that situation does not stem from me locking my family in a closet after I told them something personal. It comes from the social expectation that they respect the context of the situation.

There are certain structural assumptions baked into this unmediated scenario. First, and most importantly, there is an assumption in everyday interactions that conversations are private-by-default, public through effort. In unmediated situations, publicity takes effort. We have to consciously tell other people what we hear. Shouting to the entire town square is a lot harder than telling just a few people. Even when we share in public places, there’s a huge difference between sitting in a cafe talking with a friend and screaming to the entire room. Sure, people can overhear us in the cafe. And they do. But that doesn’t mean that they’re in the conversation. Sociologist Erving Goffman noted that there’s a societal value of “civil inattention.” Even when we can overhear conversations, we generally try to not listen. Doing so is a way of indicating that we respect others’ space. This isn’t universal and people are always jumping into conversations that they’re not a part of. But all of the parties know that they’re “butting in.”

What’s different about the Internet is not about a radical shift in social norms. What’s different has to do with how the architecture shifts the balance of power in terms of visibility. In online public spaces, interactions are public-by-default, private-through-effort, the exact opposite of what we experience offline. There is no equivalent to the cafe where you can have a private conversation in public with a close friend without thinking about who might overhear. Your online conversations are easily overheard. And they’re often persistent, searchable, and easily spreadable. Online, we have to put effort into limiting how far information flows. We have to consciously act to curb visibility. This runs counter to every experience we’ve ever had in unmediated environments.

When people participate online, they don’t choose what to publicize. They choose what to limit others from seeing. Offline, it takes effort to get something to be seen. Online, it takes effort for things to NOT be seen. This is why it appears that more is public. Because there’s a lot of content out there that people don’t care enough about to lock down. I hear this from teens all the time. “Public by default, privacy when necessary.” Teens turn to private messages or texting or other forms of communication for intimate interactions, but they don’t care enough about certain information to put the effort into locking it down. But this isn’t because they don’t care about privacy. This is because they don’t think that what they’re saying really matters all that much to anyone. Just like you don’t care that your small talk during the conference breaks are overheard by anyone. Of course, teens aren’t aware of how their interactions in aggregate can be used to make serious assumptions about who they are, who they know, and what they might like in terms of advertising. Just like you don’t calculate who to talk to in the halls based on how a surveillance algorithm might interpret your social network.

I’d particularly recommend “Making Sense of Privacy and Publicity” and “Privacy and Publicity in the Context of Big Data“. As danah points out, social media conversations essentially *require* sharing personally identifying information. But it’s personally embarrassing information that people don’t want spread.