What if newspapers published not just stories but databases? Dan Conover’s vision for the future of newspapers is inspired in part by his first reporting job, for NATO:

When we spotted something interesting, we recorded it in a highly structured way that could be accurately and quickly communicated over a two-way radio, to be transcribed by specialists at our border camp and relayed to intelligence analysts in Brussells.

The story, says Conover, is only one aspect of reporting. The other part? Gathering structured metadata, which could be stored in a database—or expressed as linked data. ((Some news organizations, like the New York Times (see Linked Open Data) and the BBC (overview, tech blog) are already embracing linked data.))

Newspapers already have classification systems and professional taxonomists. The New York Times’ classifications system, in use since 1851, now aggregates stories from the archives in Times Topics, a website and API. ((I delved into Times Topics’ taxonomy and vocabulary in an earlier post.))

What if, in addition to these classifications, each story had even more structured metadata?

Capturing metadata ranges from automatic to manual. Some automatic capture is already standard (timestamps) or could be (saving GPS coordinates from a photo or storing timestamps), and some information needing manual capture (like the number of alarms of a fire) is already reported.

Dan compares the “old way” with his “new way”:

The old way:

Dan the reporter covers a house fire in 2005. He gives the street address, the date and time, who was victimized, who put it out, how extensive the fire was and what investigators think might have caused it. He files the story, sits with an editor as it’s reviewed, then goes home. Later, he takes a phone call from another editor. This editor wants to know the value of the property damaged in the fire, but nobody has done that estimate yet, so the editor adds a statement to that effect. The story is published and stored in an electronic archive, where it is searchable by keyword.

The new way:

Dan the reporter covers a house fire in 2010. In addition to a street address, he records a six-digit grid coordinate that isn’t intended for publication. His word-processing program captures the date and time he writes in his story and converts it to a Zulu time signature, which is also appended to the file.

As he records the names of the victimized and the departments involved in putting out the fire, he highlights each first reference for computer comparison. If the proper name he highlights has never been mentioned by the organization, Dan’s newswriting word processor prompts him to compare the subject to a list of near-matches and either associate the name with an existing digital file or approve the creation of a new one.

When Dan codes the story subject as “fire,” his word processor gives him a new series of fields to complete. How many alarms? Official cause? Forest fire (y/n)? Official damage estimate? Addresses of other properties damaged by the fire? And so on. Every answer he can’t provide is coded “Pending.”

Later, Dan sits with an editor as his story is reviewed, but a second editor decides not to call him at home because he sees the answer to the damage-estimate question in the file’s metadata. The story is published and archived electronically, along with extensive metadata that now exists in a relational database. New information (the name of victims, for instance) automatically generates new files, which are retained by the news organization’s database but not published.

And those information fields Dan coded as “Pending?” Dan and his editors will be prompted to provide that structured information later — and the prompting will continue until the data set is completed.

– Dan Conover in The “Lack of Vision” thing? Well, here’s a hopeful vision for you

And that data set? It might even be saleable, even though each individual story had perhaps been given away for free. Dan highlights some possibilities, and entire industries have grown around repackaging free and non-free data (e.g. U.S. Census data, phone book data). I think of mashups such as Everyblock and hyperlocal news sites like outside.in.

Salmon Protocol: Comments Swimming Upstream

Salmon, an aggregation protocol, is championed by Google’s John Panzer, and described as an “an open, simple, standards-based solution” for “unifying the conversations”.

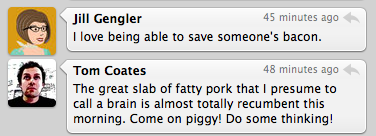

‘Conversations’ is deliberately plural, I think, to evoke the many conversations, invisible to one another: “The comments, ratings, and annotations increasingly happen at the aggregator and are invisible to the original source.”

Using Salmon, an aggregator pushes comments back to a “Salmon endpoint” (via POST). These can be published (or moderated) upstream at the original source. See also the summary of the Salmon protocol.

Comments swimming upstream…

Tags: activity streams, aggregation, distributed commenting, distributed sources, Salmon protocol

Posted in information ecosystem, social web | Comments (0)